CLINICAL METHODS1

LEARN THROUGH YOUR COURSE AND FORTIFY ALL YOUR WEAKNESS WITH KNOWLEDGEOUMA

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS

The Patient def;

The word 'patient' is derived from the Latin patiens, meaning sufferance or forbearance.

The overall purpose of medical practice is to relieve suffering. In order to achieve this purpose, it is important to make a diagnosis through history taking, physical examination, relevant investigations and interpretation of the results which shall be important in the approach to design an appropriate scheme of management for each patient.

Clinical methods

The skills clinicians use to achieve the aim of excellence in clinical practice.

These skills evolve and change as new techniques and concepts arise, and as the doctor develops in experience and maturity.

Clinical methods are acquired by a combination of study and experience, and there is always something new to learn.

The initial aims of any first consultation are to understand the patient's own perception of their problem and to start or complete the process of diagnosis.

This double aim requires a knowledge of disease and its patterns of presentation, together with an ability to interpret a patient's symptoms and signs.

Appropriate skills are needed to elicit the symptoms from the patient's description and conversation, and the signs by observation and physical examination.

Difficulties posed by assessing the patients themselves, or by the variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds found in modern life, must be accepted and factored into the interpretation of the data acquired during the consultation.

This requires not only experience and considerable knowledge of people in general, but also the skill and interest in people to strike up a relationship with a range of very different individuals.

There are two main steps to making a diagnosis:

- To establish the clinical features by history and examination - this represents the clinical database

- To interpret the clinical database in terms of disordered function and potential causative pathologies, whether physical, mental, social, or a combination of these.

Communication Skills in Clinical Practice

Introduction

Communication skills are notoriously hard to describe. There are too many possible situations that you might encounter to be able to draw rules or guidelines.

In addition, your actions will depend greatly on the personalities present—not least of which your own!

Communication models

- Patient-centered communication

In recent years, there has been a significant change in the way healthcare workers interact with patients. The biomedical model has fallen out of favor and instead, an appreciation has evolved that the patient has a unique experience of the illness.

This experience involves the social, psychological, and behavioral effects of the disease.

Some authors refer to this approach as the biopsychosocial model, which focuses on the patient in a more encompassing way.

2. The biomedical model

The provider is in charge of the consultation and examination.

Focus is on disease management.

Power and decision-making are shared

Address and treat the whole patient.

Key points in the patient-centered model

Explore the disease and the patient’s experience of it:

Understand the patient’s ideas and feelings about the illness.

Appreciate the illness’s impact on the patient’s quality of life and psychosocial well-being.

Understand the patient’s expectations of the encounter.

Understand the whole person:

- Family

- Social and work environment

- Beliefs

- Find common ground on disease management.

- Establish the doctor–patient relationship.

- Be realistic:

- Priorities for treatment

- Resources

Confidentiality;

As a doctor, health-care provider, or student, you are party to personal and confidential information.

There are also times when confidentiality must or should be broken as seen later.

The essence of day-to-day practice is: Never tell anyone about a patient unless it is directly related to his or her care and you have permission.

This includes relatives, which can be very difficult at times, particularly if a relative asks you directly about something confidential.

You can reinforce the importance of confidentiality to relatives and visitors. If asked by a relative to speak about a patient, it is a good idea to approach the patient first and ask their permission, within full view of the relative.

You can also seek permission from the patient in anticipation of such queries.

This rule also applies to friends outside of medicine.

As care providers, we come across many amazing, bizarre, amusing, or uplifting stories on a day-to-day basis, but like any other kind of information, these should not be shared with anyone.

If you do intend to use an anecdote in public, at the very least you should ensure that there is nothing in your story that could possibly lead to the identification of the person involved.

If you are in a small community, it is best to avoid sharing anything, lest you undermine your reputation as a professional.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS (Cont' 1)

Essential considerations in communication;

Patients are entrusting their health and personal information to you—they want someone who is confident, approachable, competent, and, above all, trustworthy.

First impressions count—and studies have consistently shown that your appearance (clothes, hair, makeup) has a great impact on patients’ opinion of you and their willingness to interact with you.

Part of that intangible professionalism comes from your image.

The white coat is still part of medical culture for students and most providers. Fashions in clothing change rapidly, but some basic rules still apply:

Neutralize any extreme tastes in fashion that you may have.

Men and women should wear appropriate professional attire.

Women may wear skirts or slacks but the length of the skirts should not raise any eyebrows.

Necklines should not be revealing—no décolletage (not revealing the cleveage)!

The belly should be covered—no bare midriffs!

The shoulders, likewise, should be covered.

Shoes should be polished and clean.

Clean surgical scrubs may be worn, if appropriate.

Hair should be relatively conservatively styled and no hair should be over the face. Wear long hair tied up.

Personal appearance….

Your name badge should be clearly visible, even if you don’t like your picture.

Stethoscopes are best carried or held in a coat pocket—worn at the neck is acceptable but a little pretentious, according to some views.

Try not to tuck items in your belt—use pockets or belt-holders for cell phones, keys, and wallets.

Psychiatry, pediatrics, and a handful of other specialties require a different dress code, as they deal with patients who require differing techniques for bonding with the health-care professional.

If in a hospital setting, make sure that your discussion with a patient is not during an allocated quiet time or disturbing to the patient’s roommate.

You should also avoid mealtimes or when the patient’s long-lost relative has just come to visit.

If you plan to move the patient from the bed to an exam room, ask the supervising doctor (if not you) and the nursing staff, and let all concerned know where you have gone in case the patient is needed.

Students, doctors, and other medical providers tend to see patients on hospital floors filled with distractions that can break up the interaction

Often such meetings are necessary during the course of the day. However, if you need to discuss an important matter that requires concentration from both of you, consider the following conditions:

The room should be quiet, private, and free from disturbances.

There should be enough seating for everyone.

Chairs should be comfortable enough for an extended conversation.

Arrange the seats close to yours, with no intervening tables or other furniture.

Essential Communication Rules

1. Avoid medical jargon

Medical personnel are so immersed in jargon that it becomes part of their daily speech.

The patient may not understand the words or may have a different idea of their meaning.

Technical words such as myocardial infarction are in obvious need of avoidance or explanation.

Consider also terms such as exacerbate , chronic ,numb , and sputum —these may seem obvious in meaning to you but not to the patient.

You may think that some terms such as angina and migraine are so well known that they don’t need explanation, but these are very often misinterpreted.

Some examples of words with varied interpretations between patient and doctor

2. Remember names

Forgetting someone’s name is what we all fear; it is relatively easy to disguise by simple avoidance. However, using the patient’s name will make you appear to be taking a greater interest in them.

It is particularly important that you remember the patient’s name when talking to family members.

Getting the name wrong is embarrassing and can seriously undermine their confidence in you.

Aside from actually remembering the name, it is a good idea to have it written down and within sight—on a piece of paper in your hand, on the chart, or on the desk. It is a best practice to confirm the identity of the patient, using two identifiers (name, date of birth [DOB]), before you read results from the chart or electronic medical record (EMR). To be seen glancing at the name is forgivable; patients would rather have you double check than bluff your way through an interview.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS (Cont' 2)

How

to begin an encounter with a patient;

Getting started

The start of an encounter is important but is fraught with potential difficulties.

There are no hard-and-fast rules.

Issues you should take into consideration include the following:

- Are you using a language the patient can understand?

- Can the patient hear you?

1. Greeting

Beware of saying “good afternoon” or “good morning.” These greetings can be inappropriate if you are about to break some bad news or if there is another reason for distress. Consider instead using a simple “hello.”

2. Shaking hands

A traditional greeting, shaking hands will be readily accepted by most patients, but it can also present challenges (think of patients with severe arthritis of the hands).

While physical contact always seems friendly and can warm a person to you, a handshake may be seen as overly formal by some and inappropriate by others.

Consider using some other form of touch, such as a slight guiding hand on the patient’s arm as they enter the room or a brief touch to the forearm.

Introductions; This is a minefi eld! You may wish to alter your greeting depending on the circumstances—choose terms that suit you.

3. Title—patient

Older patients may prefer to be called “Mr.” or “Mrs.”; younger patients would find this odd. For female patients whose marital status you don’t know, you can try using “Ms.,” although some younger or married patients may find this term offensive.

Calling the patient by their first name may be considered too informal by some patients. A change to using the family name mid-way through the encounter may appear unfriendly or could indicate that something has gone wrong with the interaction.

There are no rules here; use common sense to judge the situation at the time. When unsure, the best option is always to ask.

“Is it Mrs. or Miss Onyango?” “How would you like to be addressed?”

4. Title—you

The title doctor has always been a status symbol and a badge of authority—within the health-care professions at least.

Young doctors may be reluctant to part with the title so soon after acquiring it, but these days, when office visits are becoming two-way conversations between equals, patients may expect equity in the way they are addressed.

Many patients will simply call you “doctor” and the matter doesn’t arise.

We prefer using formality initially, then using first names if circumstances seem appropriate. Some elderly patients prefer—and expect—a certain level of formality, so each situation has to be judged.

Mid-level providers should follow the conventions of the health-care setting they are in. Formality is appropriate in many settings; however, most mid-level providers are more comfortable using first names.

5. Standing

Although this might be considered old-fashioned by some younger people, standing is a universal mark of respect. You should stand when a patient enters a room and take your seat at the same time as them.

You should also stand as they leave, but if you have established a good rapport during the visit, this isn’t absolutely necessary.

You may notice that patients stand when you enter the exam room. Put them at ease and acknowledge this gesture as well.

General principles of Communication

General principles of Communication

1. Demeanor

Give the patient your full attention. Appear encouraging with a warm, open manner.

Use appropriate facial expressions—don’t look bored!

2. Define your role

Along with the standard introductions, you should always make it clear who you are and what your role is.

You might also wish to introduce your team members, if appropriate.

In this era, when patients see so many health-care providers during the course of a hospitalization, it is helpful to write the team names down for them.

Style of questioning

- Open questions vs. closed questions

- Open questions are those for which any answer is possible:

- “What’s the problem?”

- These enable patients to give you the true answer in their own words.

- Be careful not to lead the patient or cut them off with closed questions.

- Compare “How much does it hurt?” with “Does it hurt a lot?” The first question allows the patient to tell you how the pain feels on a wide spectrum of severity; the second one leaves the patient only two options and will not give a true reflection of the severity.

- Multiple-choice questions

Often, patients have difficulty with an open question if they are not quite sure what you mean.

A question about the character of pain, for example, is rather hard to formulate, and patients will often not know what you mean (“What sort of pain is it”; “What does it feel like, exactly?”).

In these circumstances, you may wish to give them a few examples, but leave the list open-ended for them to add their own words. You must be very careful not to give the answer that you are expecting from them.

For example, a patient whom you suspect has angina (“crushing” pain) you could ask the following: “What sort of a pain is it—burning, stabbing, or aching, for example?”

8. Clarifying questions

Use clarifying questions to get the full details: “When you say ‘dizzy’, what exactly do you mean?”

9. Reflective comments

Use reflective comments to encourage patients to continue and reassure

them that you are following the story: “Yes, I see that.”

Staying on topic

You should be directive but polite when keeping patients on the topic you want or moving them on to a new topic.

Don’t be afraid to interrupt them—some patients will talk for hours if you let them!

“Before we move on to that, I would just like to get all the details of this dizziness”.

“We’ll come to that in a moment.”

Recognize potentially offensive or embarrassing questions. Explain why it is necessary to ask these questions, to put the patient more at ease.

“This may be an uncomfortable question, but I need to know…”

Eye contact

Make eye contact and look at the patient when he or she is speaking.

Make a note of eye contact next time you are in conversation with a friend or colleague.

In normal conversations, the speaker usually looks away while the listener looks directly at the speaker. The roles then change when the other person starts talking, and so on.

In the medical situation, while the patient is speaking, you may be tempted to make notes, read the referral letter, look at a test result, or check the EMR—you should resist this urge and stick to the customary rules of eye contact.

Adjusting your manner

You would clearly not talk to another provider as you would to someone with no medical knowledge. In much the same way, you should try to adjust your manner and speech according to the patient’s educational level. This is can be extremely difficult—you should not make assumptions about intellect or understanding solely on the basis of educational history.

Even the most educated patient can have low health literacy.

A safe approach is to start in a relatively neutral way and then adjust your manner and speech according to what you see and hear in the first minute or two of the interaction, but be alert to whether this is effective and make changes accordingly.

Understand that patients want to please and seem agreeable and may say “yes” when they really don’t understand

Interruptions

- Apologize to the patient if you are interrupted in the process of clerkship.

- Don’t take offence or get annoyed

- As well as being directly aggressive or offensive, people may be thoughtless in their speech or manner and cause offence when they don’t really mean to.

- As a professional, you should rise above this situation.

Communicating with deaf patients

- People who are hard of hearing may cope with this problem by using a hearing aid, lip-reading, or sign language. Whichever technique is used (if any), some simple rules should always apply:

- Speak clearly but not too slowly.

- Don’t repeat a sentence if it is misunderstood—say the same thing in a different way.

- Write things down, if necessary.

- Use plain English and be succinct.

- Be patient and take the time to communicate properly.

- Check understanding frequently.

- Consider finding an amplifier—many geriatric floors or clinics will have one available.

- Lip-readers

Patients who are able to lip-read do so by looking at the normal movements of your lips and face during speech.

Exaggerating movements or speaking loudly will distort these movements and make it harder for them to understand you.

In addition to the points above, when talking to lip-readers

10. Maintain eye contact.

11. Don’t shout.

12. Speak clearly but not too slowly.

13. Do not exaggerate your oral or facial movements.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS (Cont' 3)

Cross-cultural communication

Cultural background and tradition may have a large influence on disease management.

Beliefs about the origin of disease and prejudices or stigma surrounding the diagnosis can make dealing with the problem challenging.

Be aware of all possible implications of a person’s cultural background.

For example, a Muslim may not take anything by mouth in the daylight hours during Ramadan. This may have serious implications for medication management, particularly for chronic diseases such as diabetes or hypertension.

Even something as benign (to you) as eye contact may have important cross-cultural implications.

For most individuals eye contact is desired, but for many Native American and Asian cultures, it carries negative connotations.

Above all, be aware of prejudice—yours and theirs. If you are not aware of cultural implications when seeing a patient of a different culture, ask for their input.

Interpreters

Interpreters maybe required for the:

- Patients with Limited English Proficiency (LEP)

- Those with hearing disabilities

Official communicators are bound by a code of ethics, impartiality, and confidentiality; friends and relatives are not.

It is often impossible to be sure that a relative is passing on all that is said in the correct way.

Sometimes, especially in urgent situations, the patient’s children are used to interpret. This is clearly not advisable for a number of reasons.

This places too much responsibility on the child, and the child may not be able to explain difficult concepts.

Conversations about sex, death, or other difficult topics are unsuitable for children to take part in; if they do, this will impede optimal communication.

Using an official interpreter

Before you start

- Brief the interpreter on the situation, and clarify your role and the work of the department, if necessary.

- Allow the interpreter to introduce themselves to the patient and explain their role.

- Arrange seating so that the patient can see both the interpreter and health-care provider easily.

- Allow enough time (at least twice as long as normal).

- During the exchange

- Speak to the patient, not the interpreter. This may be hard to do at first, but you should speak to and look at the patient at all times.

- Be patient—some concepts are hard to explain.

- Avoid complex terms and grammar.

- Avoid jargon.

- Avoid slang and colloquialisms that may be hard to interpret correctly.

- Check understanding frequently.

The interpreter may also provide information on the patient’s culture to assist in the communication.

Finishing off

- Check understanding.

- Allow time for questions.

- Take the time to debrief with the interpreter.

- If the conversation has been distressing, offer the interpreter support and let their employer know, if appropriate.

Written information

- If interpreting written information, read it out loud.

- The interpreter may not necessarily be able to translate written language as easily.

Imparting information

- There are some guidelines for imparting any information—good or bad—to a patient:

- Identify the topic for discussion.

- Identify the people present and ask if there is anyone else that they would like to be there.

- Establish previous experience and knowledge.

- Keep sentences and explanations short and simple.

- Repeat important information.

- Allow time for feedback and questions, and check understanding.

- Schedule time for follow-up.

- Be honest!

The importance of silence

In conversations with friends or colleagues, your aim is often to avoid silence, using filler noises such as “um” and “ah” while pausing.

In medical situations, by contrast, silences should be embraced and used to extract more information from the patient. Use silence in order to listen.

Practice is needed, as the inexperienced may find this situation uncomfortable.

It is often useful, however, to remain silent once the patient has answered your question.

You will usually find that the patient will start speaking again, and often provide useful and enlightening facts that you would otherwise not have gleaned.

Angry patients

- With angry patients, use body language to take charge of the situation without appearing aggressive. Throughout the exchange, you should remain polite, avoiding confrontation, and resist becoming angry yourself.

- Look to your own safety first.

- Calm the situation, then establish the facts of the case. Anger is often secondary to some other emotion, such as loss, fear, or guilt.

- Acknowledge the patient’s emotions through statements such as the following:

- “I can see that this has made you angry.”

- “It’s understandable that you should feel like this.”

- Steer the conversation away from the area of unhappiness and toward the positive and plans, to move the situation forward.

- Don’t incriminate colleagues—the patient may remember your throwaway comments, which could come back to haunt you. Avoid remarks like “he shouldn’t have done that.”

- Emphasize any grounds for optimism or plans for resolving the situation and putting things right.

Telephone and e-mail communication

The essential rule of confidentiality is that you must not impart personal information to anyone without the express permission of the patient concerned—except in a few specific circumstances.

You must not give out any confidential information over the telephone unless you are sure of the identity of the caller. All communication is best done face to face. This may cause difficulty if a relative calls to ask about the patient, but you should remain strict about this rule unless you have the expressed permission of the patient.

When discussing follow-up communication for test results, obtain the patient’s permission to leave a message on an answering machine or as voice mail. Check to see if you have their correct phone number.

E-mail communications can be very problematic, especially if you do not have a secure, encrypted system. Most health-care institutions have their own policy regarding use of e-mail, so you should know what the rules are.

Patient’s e-mails should nonetheless be answered. Some providers will call the patient back, documenting the communication in the EMR or chart. Others will ask the patient to set up an appointment.

The use of social media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) in medicine is still evolving. It is best not to use these for any patient information.

If telephone communication is essential but you are in doubt as to the caller’s identity, you may wish to take their number, check it with your records, and then call them back.

Talking about sex

This can be a cause of considerable embarrassment for the patient and for the inexperienced professional.

Sexual questions are inappropriate to ask in the presence of friends or relatives, so ask them to leave the room.

Your aim is to put the patient at ease and make responses more forthcoming.

Make no assumptions about a patient’s sexual orientation.

The key is to ask direct, clear questions and show no embarrassment.

You should maintain eye contact.

You should also show no surprise whatsoever, even if the sexual practices described differ from your own or from those that you would consider acceptable.

Try to become familiar with sexual slang and sexual practices that you might not be familiar with.

A failure to understand slang may lead to an immediate barrier in the patient interview.

In general, you should not use slang terms first. You may wish to consider mirroring the patient’s speech as you continue the conversation.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS (Cont' 4)

Breaking bad news

Students fear breaking bad news, and no one likes doing it. However, knowing that you have broken difficult news in a sensitive way and that you have helped the patient through a terrible experience can be one of the most uplifting aspects of working in health care.

Confirm all the information for yourself and ensure that you have all the information on hand, if necessary.

Speak to the nursing staff to get background information on what the patient knows, their fears, and details of their relationship with any family or friends who may be present.

Pick a quiet, private room where you won’t be disturbed.

Ensure that there is no intervening desk or other piece of furniture.

Arrange the chairs so that everyone can be seen equally.

Hand your pager and cell phone to a colleague or turn it off.

Invite a member of the nursing staff to join you, particularly if they have already established a relationship with the patient.

Remember, it is usually the nursing staff that will be dealing with the patient and relatives after you leave, so they need to know exactly what was said.

Would the patient like anyone in particular to be present?

Remember the general principles learnt earlier:

Avoid using jargon,

Speak slowly and clearly.

Establish previous knowledge

It is essential to understand what the patient already knows. The situation is very different for a patient who knows that you have been looking for cancer than that of a patient who thinks their cough is due to a cold.

“What have the other doctors told you?”

How much do they want to know?

This is key. Before you consider breaking bad news, you have to learn if the patient actually wants to hear it. Ask an open question, such as:

“Have you thought about what might be causing these problems?”

“Do you know why we’ve been doing these tests?”

You can also ask directly if they want to hear what you might have to say:

“Are you the sort of person who likes to know all the available facts?”

Warning shots when breaking bad news;

If they do want to know, you should break the news in a step-wise fashion, delivering multiple “warning shots.” This gives the patient a chance to stop you if they’ve heard enough or to ask for more information.

Keep your sentences, short, clear, and simple. A conversation may go like this:

You : I’m afraid the test results show that things are more serious than first thought.

Patient : What do you mean more serious?

You : Some of the cells look abnormal.

Patient : Do you mean that I have cancer?

You : Yes.

At any point, the patient may stop you, signaling that they don’t want to hear more about it.

Inexperienced practitioners sometimes feel that they ought to tell the patient the full story, but they must understand that many people would much rather not hear the words said aloud—this is their coping strategy and must be respected.

More than likely, this will not be your only opportunity to speak with the patient.

You : I’m afraid the test results show that things are more serious than first thought.

Patient : Just tell me what we can do next.

Allow time for information to sink in

You should allow time for each piece of information to sink in, ensuring that the patient understands all that has been said and repeating any important information.

Remember also that patients will not be able to remember the exact details of what you have said—you may need to reschedule at a later time to talk about treatment options or prognosis.

Honesty, above all else

Above all, you should be honest at all times. Never guess, predict, or lie.

The patient may break your pre-prepared flow of information, requiring you to think on your feet. Sometimes you simply can’t abide by the rules above. If asked a direct question, you must be honest and straightforward.

For example:

Breaking bad news….

You : I’m afraid the test results show more than I had thought…

Patient: Just tell me, do I have cancer

You: Yes! I am afraid you do.

Don’t rush to the positive

When told of bad news, the patient needs a few moments to let the information sink in. After the “yes” in the previous examples, you should preferably wait in silence for the patient to speak next.

The patient may break down in tears, in which case they should be offered tissues and the support of relatives, if nearby.

If emotionally distressed, the patient will not be receptive to what you say next—you may want to give them some time alone with a relative or nurse before you continue to talk about prognosis or treatment options.

Above all, you should not give false hope . The moment after the bad news has been broken can be uncomfortable, and you must fight the instinctive move to positive,-sounding statements, such as “there are things we can do”; “on the plus side . . . ”; “the good news is . . .”; or something similar.

Ending

Summarize the information given, check the patient’s understanding, repeat any information as necessary, allow time for questions, and make arrangements for a follow-up appointment or a further opportunity to ask questions again.

Obviously, you shouldn’t make promises that you can’t keep.

Don’t offer to come back that afternoon if you’re going to be in clinic!

“Do you understand everything that we’ve discussed?”

“Is there anything else that you would like to ask me?”

“I’ll plan to see you tomorrow morning. I’ll be happy to come back in the meantime if you think of anything that you’d like to ask or if you need to talk. Just ask one of the nursing staff to page me.”

Questions about time

“How long have I got?” is one of the most common questions asked, and the hardest to answer.

As always, don’t guess and don’t lie.

It’s often impossible to estimate this. Giving a figure will almost always lead to you being wrong. If you don’t know, it is perfectly acceptable to say so.

Explain that it is impossible to judge, and ask if there is any date in particular that they don’t want to miss—perhaps they want to experience Christmas or a relative’s birthday.

Don’t assume that they are asking out of fear; some people are surprisingly practical and want to put their affairs in order before their death.

Body

language

Body language: an introduction

Body language is rarely given the place it deserves in the teaching of communication skills.

There are over 600 muscles in the human body—90 in the face, of which 30 act purely to express emotion.

Changes in your position or expression—some obvious, others subtle—can heavily influence the message that you are communicating.

We’ve all met someone and thought, “I didn’t like him” or “she seemed trustworthy.” Often these impressions of people are not built on what is said but the manner in which people handle themselves. You subconsciously pick up cues from the other person’s body.

Being good at using body language means having awareness of how the other person may be viewing you and getting your subconscious actions and expressions under conscious control.

If done well, you can influence the other person’s opinion of you, make them more receptive to your message, or add particular emphasis to certain words and phrases.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN CLINICAL METHODS (Cont' 5)

Body language variations;

Touching

Touching is one of the most powerful forms of nonverbal communication and needs to be managed with care.

Greeting: Touch is part of greeting rituals in most cultures. It demonstrates that you are not holding a weapon and establishes intimacy.

Shaking hands: There are many variations. The length of the shake and the strength of the grip impart a huge amount of information. For added intimacy and warmth, a double-handed grip can be used. For extra intimacy, one may touch the other’s forearm or elbow. *

Dominance: Touch is a powerful display of dominance. Touching someone on the back or shoulder demonstrates that you are in charge—this can be countered by mirroring the action back.

Sympathy: The lightest of touches can be very comforting and is appropriate in the medical situation where another type of touch may be misread as dominance or intimacy (you shouldn’t hug a patient you’ve just met!). Display sympathy by a brief touch to the arm or hand.

Open body language

A cluster of movements are associated with seeming open . The most significant part of this is the act of opening—signaling a change in the way you are feeling.

Openness demonstrates that you have nothing to hide and are receptive to the other person.

Openness encourages openness.

This can be used to calm an angry situation or when asking about personal information.

The key is to not have your arms or legs crossed in any way. The key is to not have your arms or legs crossed in any way.

Arms open: either at your side or held wide. Even better, hold your hands open and face your palms toward the other person.

Legs open: this does not mean legs wide, rather, legs not crossed. You may hold them parallel. The feet often point toward something of subconscious interest to you—point them at the patient!

Emphasis

You can amplify your spoken words with your body, usually without noticing it. Actions include nodding your head, pointing, or other hand gestures.

A gesture may involve your entire body.

Watch TV news anchors—often only their heads are in view, so they emphasize with nods and turns of their heads much more than one would during normal conversation.

Synchrony: This is key. Time your points of the finger, taps of the hand on the desk, or other actions with the words you wish to emphasize.

Precision: Signal that the words currently being spoken are worth paying attention to with delicate, precise movements. You could make an ‘O’ with your thumb and index finger or hold your hands such that each finger is touching its opposite counterpart—like a splayed prayer position.

Eye level

This is a very powerful tool. In general, the person with a higher eye level is in control of the situation.

You can use this tactic to your advantage. When asking someone personal questions or when you want them to open up, position yourself such that your eyes are below theirs, meaning they have to look down at you slightly. This makes them feel more in control and comfortable.

Likewise, anger often comes from a feeling of lack of control—put the angry person in charge by lowering your eye level—even if that means squatting next to them or sitting when they are standing.

Conversely, you may raise your eye level to take charge of a difficult situation; looking down on someone is intimidating.

Stand over a seated person to demonstrate that you are in charge.

Watch and learn

You should watch others and yourself and consider what messages are being portrayed by nonverbal communication.

Stay aware of your own movements, and consider intentionally changing what would normally be subconscious actions to add to, or alter, the meaning of your speech.

Written communication

Written communication

Medical notes serve a number of purposes. The most important ones are as follows:

They are a record of the patient’s illness, treatments, and medical encounters, for use by other medical practitioners in the future.

They are the only record of your actions—and the means by which you may be judged in case of future disputes.

They are a record of events for the purposes of clinical audit.

How to write in the notes

Your entries in the notes should be tidy and legible. All entries should include the following:

- Date

- Time

- Medical information

- Signature (also print your name if your handwriting is illegible).

- Identity of the inscriber

- Contact number (pager and/or cell phone)

Use black ink only (blue often doesn’t photocopy easily and can fade).

What to write in the notes

Everything that occurs should be recorded. If it isn’t written down, it didn’t happen!

Remember especially to record discussions with relatives and the details of what the patient has been told of diagnoses.

There are no specific rules on how things should be written—there are a number of conventions introduced throughout the book.

In general, entries should be easily understood by another staff member.

Standard examination drawings

The essential rule is that the record you make should be easily understood by another person. If it is hard to describe where the cut on the patient’s foot is, draw it!

There are a number of diagrams that, though not official, are widely used and accepted as standard.

Law, ethics, and communication

It is also worth knowing the four bioethical principles, about which much has been written elsewhere.

Four bioethical principles

- Autonomy: a respect for the individual and their ability to make decisions regarding their own health

- Beneficence: acting to the benefit of patients

- Nonmalificence: acting to prevent harm to the patient

- Justice: fairness to the patient and the wider community when considering the consequences of an action

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is closely linked to the ethical principles described above.

Maintaining a secret record of personal information shows respect for the individual’s autonomy and their right to control their own information.

There is also an element of beneficence, whereas releasing the protected information may cause harm.

Breaking confidentiality

There are a number of circumstances in which confidentiality can, or must, be broken. The exact advice varies between different bodies.

In general, confidentiality may be broken in the following situations:

- With the consent of the individual concerned

- If disclosure is in the patient’s interest but consent cannot be gained If required by law

- When there is a statutory duty, such as reporting of births, deaths, and abortions, and in cases of certain communicable diseases

- If it is overwhelmingly in the public interest

- If it is necessary for national security or when prevention or detection of a crime may be prejudiced or delayed

- In certain situations related to medical research

Consent and capacity

There are three main components to valid consent. To be competent (or have capacity) to give consent, the patient

Must understand the information that has been given

Must believe that information

Must be able to retain and evaluate the information to make a decision

In addition, for consent to be valid, the patient must be free from any kind of duress.

It should be noted that an assessment of capacity is valid for the specific decision at hand. It is not an all-or-nothing phenomenon—you cannot either have capacity or not.

The assessment regarding competence must be made for each new decision faced.

Law, ethics, and communication….

Young people and capacity

All persons aged 18 and over are considered to be a competent adult unless there is evidence to the contrary.

People between 16 and 18 years of age may be treated as adults if they are covered by statutes regarding emancipated minors. However, the refusal of a treatment can be overridden by the courts.

Children age 16 and younger are considered competent to give consent if they meet the three conditions mentioned previously.

However, their decisions can be overridden by the courts or by people with parental responsibility.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: Summary

- Effective communication in clinical medicine is an essential skill for patient management.

- During an encounter with a patient, all the approaches in communication can be used depending on the unique setting.

- During communication, a clinician should identify any possible barrier and address them appropriately for effective communication.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 1: References

- Glynn, M., Deake, W. M., and Hutchson R., (2012). Hutchison’s Clinical Methods: An integrated Approach to clinical practice. Edinburgh Elsevier latest edition.

- Houghton A.R, Gray D. and Chamberlain, E.R. (2010). Chamberlains Clinical signs and symptoms in Clinical Medicine. London, Hodder Arnold.

- Lumley, J.S.P and Bailey H. (2001) Hamilton Baileys physical signs: Demonstration of physical signs: in Clinical Surgery.

- Macleod J. Douglas G. Nicol, E. F. and Robertson C. (2009). Macleod’s Clinical Examination Edinburg; Churchill Livingstone/ Elsevier

- Tally N. J. and O’ Conner, S. (2001). Clinical examination: A Systemic Guide to physical diagnosis. Diagnosis, Oxford: Blackwell science.

- Thomas J. and Mohaghan T. (2014) Oxford Hand book of clinical examination and practical skills. Oxford University press.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:HISTORY TAKING

The history

Areas to cover:

- Patient profile (PP)

- Chief complaint (CC)

- History of present illness (HPI)

- Past medical history (PMH)

- Allergies

- Drug history

- Alcohol

- Smoking

- Family history (FH)

- Social history (SH)

- Review of systems (ROS)

- The elderly patient

- The pediatric patient

History-taking

- The history is a patient’s account of their illness together with other relevant information you have gleaned from them.

- There is a tried and tested standard sequence that you should conform to and is used by all providers.

- It is good practice to make quick notes while talking to the patient that you can use to write a thorough history afterward—don’t document every word they say, as this breaks up your interaction!

- By the end of the history-taking you should have a good idea of a diagnosis or have several differential diagnoses in mind.

- The examination is your chance to confirm or refute these through the acquisition of more information.

- History-taking is not a passive process.

- You need to keep your wits about you and gently guide the patient in giving you relevant information through use of all the communication skills described earlier.

Different approaches;

Many people list information on smoking and alcohol as part of the social history.

Others feel that these factors have such a significant impact on health that they are more appropriately placed as part of the past medical history, rather than as what the patient does in their spare time.

It is good practice in medicine to watch what other practitioners do and adapt the parts that you feel are done well to your own style, making them part of your own routine.

The standard history framework

- Patient profile (PP)

- Chief complaint (CC)

- History of the present illness (HPI)

- Past medical history (PMH)

- Allergies

- Drug history

- Alcohol

- Smoking

- Family history (FH)

- Social History (SH)

- Occupational History

- Review of Systems (ROS)

There are many situations in which the patient may be unable to give a history e.g.,

- Unconscious,

- Delirious,

- Demented, or

- Dysphasic.

In these situations, you should make an effort to speak to all who can help you fill in the gaps—regarding not only what happened to the patient but also their usual medication, functional state, living arrangements, and so on.

When taking a history from a source other than the patient, be sure to document clearly that this is the case and the reason(s) for the patient being unable to speak for themselves.

Useful sources of information include the following:

- Relatives, guardians, and cohabitants

- Close friends and roommates

- Primary care physician (PCP) or other members of the primary care team

- Pharmacist

- Staff at the nursing home or residential or other facility

- Ambulance personnel

- Anyone who witnessed the event.

Patient profile (PP)

This is the essential identifying and biographic information required by the facility.

Typically included in the PP will be the patient’s name, address, and DOB.

Other information included in the PP may include:

- Age

- Religion

- Nationality

- Marital status

Contact information as requested by the individual facility

Chief complaint (CC)

This is the patient’s chief symptom(s) in their own words.

It should generally be no more than a single sentence.

If the patient has several symptoms, present them as a list that you can expand on later in the history.

Ask the patient an open question, such as:

- “What’s the problem?”

- “What made you come to the office?”

Each provider will have their own style.

You should choose a phrase that suits you and your manner (one of the authors favors saying.

E.g. “tell me the story”, after a brief introduction.

The question “What brought you here?” usually brings the response “an ambulance,” “my feet,” or “the taxi”—each patient being under the impression that they are the first to crack this joke. This question is thus best avoided.

Remember, the CC is expressed in the patient’s words. “Hemoptysis” is rarely a presenting complaint, but “coughing up blood” may well be!

NB: This initial part of the history is particularly important and highly dependent on the skill of the doctor. It is very tempting to interrupt too early, but once interrupted the patient rarely completes what they were intending to say. Even when they appear to have finished giving their reasons for the consultation, always ask if there are any more broad areas that still need discussion, before beginning to discuss each in more detail.

History of the presenting illness (HPI)

Here you are asking about and documenting details of the presenting complaint.

By the end of taking the HPI, you and readers of the record should have a clear idea about:

The nature of the problem and of exactly how and when it started,

How the problem has progressed over time

What impact it has had on the patient in their general physical health, psychology, and social and working lives

What remedies, including earlier medical interventions received

The HPI is best tackled in two phases.

Phase I

Ask an open question (as for the CC) and allow the patient to talk through what has happened for about 2 minutes. Don’t interrupt!

Encourage the patient with nonverbal responses and take discreet notes.

This allows you to make an initial assessment of the patient in terms of:

Education level

Personality, and

Anxiety.

Using this information, you can adjust your responses and interaction. It should also become clear to you exactly what symptom the patient is most concerned about.

Second phase

In the second phase, you should revisit the whole story, asking more detailed questions.

It may be useful to say, “I’d just like to go through the story again, clarifying some details.”

This is your chance to verify time-lines and the relation of one symptom to another. You should also clarify pseudo- medical terms (e.g., exactly what does the patient mean by “vertigo,” “flu,” or “rheumatism”?).

Remember, this should feel like a conversation, not an interrogation!

For each symptom, determine

The exact nature of the symptom

- The onset

- Date it began

- How it began (e.g., suddenly, gradually—over how long?)

- If the symptom is long- standing, why is the patient seeking help now?

- Previous occurrences and frequency

- Is the symptom constant or intermittent?

- How long does it last each time?

- What is the exact manner in which it comes and goes?

- Change over time

- Is it improving or deteriorating?

- Exacerbating factors

- What makes the symptom worse?

- Relieving factors

- What makes the symptom better?

- Associated symptoms

- For pain, determine:

- Site (where is the pain worst—ask the patient to point to the site with one finger)

- Radiation (does the pain move anywhere else?)

- Character (i.e., dull, aching, stabbing, burning)

- Severity (scored out of 10, with 10 being the worst pain imaginable)

- Mode and rate of onset (how did it come on—over how long?)

- Duration

- Frequency

- Exacerbating factors

- Relieving factors

- Associated symptoms (e.g., nausea, dyspepsia, shortness of breath)

A mnemonic for remembering the important factors in analyzing pain or a symptom is O3PQRST. It includes the significant factors:

Onset, Previous occurrences, Provoking factors, Palliative factors (including prescribed and home treatments attempted), Quality (such as characteristics of pain), Radiation (site of onset and any radiation), Severity, and Timing

If the symptom is long-standing, ask why the patient is seeking help now.

Has anything changed?

It is often useful to ask when the patient was last well.

This may help focus their mind on the start of the problem, which may seem distant and less important to them.

Some aspects of the patient’s past illnesses or diagnoses may have already been covered.

Here, you should obtain detailed information about past illnesses and surgical procedures.

Ask the patient if they are receiving care for anything else or have ever been to the hospital before.

Ensure that you get dates and a location for each event.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:HISTORY TAKING (Cont')

For each condition, ask the following:

- When was it diagnosed?

- How was it diagnosed?

- How has it been treated?

- For operations, ask about any previous anesthesia problems.

- Ask about immunizations.

- Have the patient provide as many specifics about types and dates of immunizations.

- Also ask about employment and insurance examinations.

Specific conditions to include in PMH

- Diabetes

- Rheumatic fever

- Jaundice

- Hypercholesterolemia

- Hypertension

- Angina

- Myocardial infarction (MI)

- Stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA)

- Asthma

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Epilepsy

- Anesthetic problems

- Blood transfusions

- Childhood illnesses and sequelae

Don’t take anything for granted!

For each condition that the patient reports having, ask exactly how it was diagnosed (where? by whom?) and how it has been treated since then.

For example:

If the patient reports “asthma,” ask;

- Who made the diagnosis

- When the diagnosis was made,

- If they have ever had lung function tests

- If they have ever seen a pulmonologist, and

- If they are taking any inhalers.

- Have they used any over-the-counter (OTC) treatments or alternative medications?

Occasionally, patients will give a long-standing symptom a medical name, which can be very confusing. In this example, the patient’s “asthma” could be how they refer to their wheeze that is due to congestive cardiac failure.

Any allergies should be documented separately from the drug history because of their importance.

Ask if the patient has any allergies or is allergic to anything if they are unfamiliar with the term allergies .

Be sure to probe carefully, as people will often tell you about their hay fever and forget about the rash they had when they took penicillin.

Ask specifically if they have had any reactions to drugs or medication; don’t forget to inquire about food or environmental allergies.

If an allergy is reported, you should obtain the exact nature of the event and decide if the patient is describing a true allergy, intolerance, or simply an unpleasant side effect.

Here you should list all the medications that the patient is taking, including the dosage and frequency of each prescription.

If the patient is unsure about their medications, confirm the drug history with the prescribing provider or pharmacy.

Take special note of any drugs that have been started or stopped recently.

You should also ask about compliance—does the patient know what dose they take? Do they ever miss doses? If they are not taking the medication, what’s the reason? Do they have any compliance aids such as a pre-packaged weekly supply?

It may also be valuable to ask if the patient is having any difficulty obtaining their medications.

The patient may consider some medications as not being drugs,

so specific questioning is required. Don’t forget to ask about the following:

Eye drops

Inhalers

Sleeping pills

Oral contraception

OTC drugs (bought at a store or pharmacy), vitamin supplements

Herbal remedies

Illicit or “recreational” drug use

You should attempt to quantify, as accurately as possible, the amount of alcohol consumed per week, and establish if the consumption is spread out evenly over the week or concentrated in a smaller period.

The CAGE questionnaire, long considered a standard in alcohol assessment, may be supplemented or possibly replaced by use of a single question: “How many times in the past year have you had X or more drinks in a day?,” where X is 5 for men and 4 for women, and a response of 1 or more times has been validated and may prove to be valuable with certain populations

In the United States and many European countries, alcohol is quantified as standard drinks. In the United States, a standard drink contains 0.54 ounces of alcohol.

Healthy People 2010 reports that males may be at risk for alcohol related problems if they drink more than 14 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks per occasion.

Likewise, females may be at risk if they drink more than seven drinks per week or three drinks per occasion.

For typical strength alcoholic beverages the following contain approximately 0.54 ounces of ethanol:

12 ounces beer

5 ounces of wine

1.5 ounces of 80 proof distilled spirits

d)Smoking

Attempt to quantify the habit in pack-years:

1 pack-year is 20 cigarettes (1 pack) per day for 1 year (e.g., 40/day for 1 year = 2 pack years;

10/day for 2 years = 1 pack-year).

Ask about previous smoking, as many patients will call themselves nonsmokers if they gave up yesterday or are even on their way to the hospital or clinic!

Remember to ask about passive smoking. An inquiry such as, “Do you smoke in your house, in your car, or around your children?” may help to raise consciousness regarding health risks for children and the issue of influencing the child’s future behavior.

Be aware of cultural issues—smoking is forbidden for Sikhs, for example, and they may take offence at the suggestion of smoking!

Family history (FH)

The FH details the following:

Makeup of the family, including age and gender of parents, siblings, children, and extended family, as relevant

Health of the family

You should ask about any diagnosed conditions in other living family members. Stating a “laundry list” of common conditions will help the patient understand conditions that you are most concerned about.

You should also document the age and cause of death for all deceased first-degree relatives and for other family members if you feel it is appropriate.

It may help to draw a family tree (genogram).

These diagrams are particularly useful in pediatric assessments, families with multiple health problems that demonstrate familial propensities, and families with hereditary conditions.

Social history (SH)

This is your chance to document the details of the patient’s personal life that are relevant to:

The working diagnosis,

The patient’s general well-being, and

The recovery or convalescence

The SH will help in understanding the impact of the illness on the patient’s functional status.

This is a vital part of the history but is often given only brief attention.

The disease and, indeed, the patient do not exist in a vacuum but are part of a community that they interact with and contribute to. Without these details, it is impossible to take a holistic approach to the patient’s wellbeing.

Establish the following in the social history:

- Marital status

- Sexual orientation

- Occupation (or previous occupations if retired)

- You should establish the exact nature of the job if it is unclear—does it involve sitting at a desk, carrying heavy loads, or traveling?

- Other people who live at the same address

- Type of accommodation (e.g., house, apartment—and on what floor)

- Does the patient own their accommodation or rent it?

- Are there any stairs? How many?

- Does the patient have any aids or adaptations in their house (e.g., rails near the bath)?

- Does the patient use any walking aids (e.g., cane, walker, scooter)?

- Does the patient receive any help on a daily basis?

- Who from (e.g., family, friends, social services)?

- Who does the laundry, cleaning, cooking, and shopping?

- Does the patient have relatives living nearby?

- What hobbies does the patient have?

- Does the patient own any pets?

- Has the patient been abroad recently or spent any time abroad in the past?

- Does the patient drive?

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:HISTORY TAKING (Review of systems)

Review of systems (ROS)

Ask the patient if they have any of the following symptoms:

General symptoms

Weight change (loss or gain), change in appetite (loss or gain), fever, lethargy, malaise

Skin symptoms

Lumps, bumps, sores, ulcers, rashes, itch

Sensory symptoms

Vision problems hearing deficits

Respiratory symptoms

Cough, sputum, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, wheeze, chest pain

Cardiovascular symptoms

Shortness of breath on exertion, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, ankle swelling, orthopnea, claudication

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Dysphagia, indigestion, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, a change in bowel habit, constipation, diarrhea, rectal blood loss

Genitourinary symptoms

Urinary frequency, polyuria, dysuria, hematuria, nocturia, menstrual, problems, impotence, urgency, post- micturition dribbling, retrograde ejaculation

Neurological symptoms

Headaches, dizziness, tingling, weakness, tremor, faint, seizures, convulsions, epilepsy, blackouts or other loss of consciousness

Psychological symptoms

Depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances

Endocrine symptoms

Intolerance to heat or cold

Musculoskeletal symptoms

Aches, pains, stiffness, swelling

The elderly patient

Obtaining a history from older people might be regarded as no greater task than that for any other patient; however, cognitive decline, deafness, and acute illness can make this difficult.

Taking a good history from older people is a skill that you will find useful in all other situations.

While the history is key for making diagnoses, it is also an opportunity for much more—your first interaction with an older patient sets important first impressions.

A skillful history not only reaps diagnostic rewards but also marks you as a competent provider who can gain trust, reassure, and communicate well with patients in any challenging situation.

Key points when handling elderly patients;

- Learn to listen

- It can be tempting to ask lots of questions to obtain every fact in the history, particularly if you are rushed.

- Doing this will not only frustrate and offend your patient (because you clearly don’t listen) but will also risk your missing important facts.

- Instead, learn to stay quiet—and listen in detail to the history of the presenting complaint, which may only be 3–4 minutes, but gives your patient a chance to be heard.

- Seemingly irrelevant detail is often useful when patients have the chance to put it in context. It often saves you time, as other key information may emerge, and you can better focus the history.

Problem lists

Patients with chronic illness or multiple diagnoses may have more than one strand to their acute presentation.

Consider breaking the history of the presenting complaint down into a problem list, e.g.,

This can often reveal key interactions between diagnoses that you might not have thought about.

Drug history in the elderly;

Remember to consider polypharmacy and that patients may not remember all the treatments they take.

Be aware that more drugs mean more side effects and less compliance, so ask which are taken and why—(older) people are often quite honest about why they omit tablets.

Many elderly individuals use supplements or alternative remedies that may interfere with your prescribed treatments, so ask about them! Eye drops, sleeping pills, and laxatives are often regarded non-medicines by patients, so be thorough and ask about each separately.

Avoid precipitating delirium due to acute withdrawal of benzodiazepines.

Finally, remember the cost of medications and the impact they have on an individual on a fixed income.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:HISTORY TAKING (Review of systems)- Cont'

Functional history in the elderly;

A comprehensive functional history is a cornerstone of your history-taking in older people— You deserve no apologies for being reminded over and over about this throughout clinical methods lessons.

Diseases may not cured or modified, but their key component—the effects on patients and their lives—might be easily transformed through manipulation of activities of daily living.

Remember to ask about support systems for the patient at home—have things resulted in a crisis for the patient because a caregiver is ill? Be polite and ask tactfully about finances and available services. Are social service benefits, such as home health and meals-on-wheels, available?

Many patients do not realize that they might be eligible, so precede your questions with an explanation that, if desired, information about resources or referral may be provided.

Social history in the elderly;

SH is exactly that and should complement the functional history.

Occupation (other than retired) can be of value when one is faced with a new diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis or bladder cancer and may give your patient a chance to sketch out more about their lives. Inquire about family—don’t assume that a relative may be able to provide help, as they may live far away; the patient may still have a spouse, but be separated.

Chat with patients about their daily lives—interests and pursuits can help distract an ill patient, give hope for the future, and act as an incentive for recovery and meaningful rehabilitation.

The pediatric patient

Obtaining a history about or from children may present additional challenges, depending on who is available to provide the history and how active the child is.

Key points in the paediatric patient;

- Learn to listen

- Remember to listen to the child in addition to the caregiver. Again, it can be tempting to ask lots of questions to obtain every fact in the history.

- Doing this may result in missed opportunities to observe the patient– caregiver interaction.

- The child who is given appropriate attention during the history may feel more engaged and be more cooperative during the exam. Instead of having the child be quiet, remember to solicit the input of your youthful patient.

- It gives them a chance to be heard. It can even save time, as key information may emerge from the unexpected source—the child.

Drug history in the paediatric patient;

Remember that parental practices may put children at risk. Ask about the use of OTC medications and alternative treatments. This is often an overlooked area when dealing with children.

Social history in the paediatric patient;

Don’t assume that a relative bringing the child in for an exam may be able to provide all the needed information.

The child may be the subject of a shared-custody agreement, or the noncustodial parent, who has minimal information about the child, may be bringing the child in. Remember to ask about formal and informal support for the patient and family during illness.

Ask tactfully about the availability of parental benefits, including sick time.

Chat with the child about their daily activities.

Garrulous Patient

- Patient is incapable of giving short simple answers

- Gives endless and inappropriate details

- Digress and repeat themselves

- May behave in such a manner due to obsession personality or anxiety therefore you should guide them politely without causing offence.

The Well-informed Patient

The Well-informed Patient

Twenty or more years ago doctors often looked after patients for a long time without really explaining their illness to them, and patients were reasonably happy about this, taking the attitude that 'the doctor knows best'.

This approach is now unacceptable, and the doctor must give the patient as much information about their illness as possible, particularly so that they can make informed choices about treatments.

This change of approach has led to many patients seeking information about their problems from other sources, particularly the Internet.

The doctor must take all this in their stride, go through the information with the patient, and help them by showing what is relevant and what is not.

In general it is much easier and more rewarding to look after well-informed patients, provided they do not fall into the very small group who have such fixed and erroneous ideas about their problems that the diagnostic and treatment process is impeded.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:Summary

- During systemic review, the affected system(s) should be reviewed in the history of presenting illness.

- All other systems not mentioned in the history are reviewed in the review of systems section.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 2:References

- Glynn, M., Deake, W. M., and Hutchson R., (2012). Hutchison’s Clinical Methods: An integrated Approach to clinical practice. Edinburgh Elsevier latest edition.

- Houghton A.R, Gray D. and Chamberlain, E.R. (2010). Chamberlains Clinical signs and symptoms in Clinical Medicine. London, Hodder Arnold.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 3: GENERAL EXAMINATION AND VITAL SIGNS

Vital Signs

Vital signs include the measurement of: temperature, respiratory rate, pulse, blood pressure and, where appropriate, blood oxygen saturation. These numbers provide critical information (hence the name "vital") about a patient's state of health. In particular, they:

- Can identify the existence of an acute medical problem.

- Are a means of rapidly quantifying the magnitude of an illness and how well the body is coping with the resultant physiologic stress. The more deranged the vitals, the sicker the patient.

- Are a marker of chronic disease states (e.g. hypertension is defined as chronically elevated blood pressure).

Most patients will have had their vital signs measured by an RN or health care assistant before you have a chance to see them. However, these values are of such great importance that you should get in the habit of repeating them yourself, particularly if you are going to use these values as the basis for management decisions. This not only allows you to practice obtaining vital signs but provides an opportunity to verify their accuracy. As noted below, there is significant potential for measurement error, so repeat determinations can provide critical information.

Getting Started: The examination room should be quiet, warm and well lit. After you have finished interviewing the patient, provide them with a gown (a.k.a. "Johnny") and leave the room (or draw a separating curtain) while they change. Instruct them to remove all of their clothing (except for briefs) and put on the gown so that the opening is in the rear. Occasionally, patient's will end up using them as ponchos, capes or in other creative ways. While this may make for a more attractive ensemble it will also, unfortunately, interfere with your ability to perform an examination! Prior to measuring vital signs, the patient should have had the opportunity to sit for approximately five minutes so that the values are not affected by the exertion required to walk to the exam room. All measurements are made while the patient is seated.

Observation: Before diving in, take a minute or so to look at the patient in their entirety, making your observations, if possible, from an out-of-the way perch. Does the patient seem anxious, in pain, upset? What about their dress and hygiene? Remember, the exam begins as soon as you lay eyes on the patient.

Temperature: This is generally obtained using an oral thermometer that provides a digital reading when the sensor is placed under the patient's tongue. As most exam rooms do not have thermometers, it is not necessary to repeat this measurement unless, of course, the recorded value seems discordant with the patient's clinical condition (e.g. they feel hot but reportedly have no fever or vice versa). Depending on the bias of a particular institution, temperature is measured in either Celcius or Farenheit. The normal temperature range is 35.5-37.5 degrees celcius. Rectal temperatures, which most closely reflect internal or core values, are approximately 0.5 degree C higher than those obtained orally.

Respiratory Rate: Respirations are recorded as breaths per minute. They should be counted for at least 30 seconds as the total number of breaths in a 15 second period is rather small and any miscounting can result in rather large errors when multiplied by 4. Try to do this as surreptitiously as possible so that the patient does not consciously alter their rate of breathing. This can be done by observing the rise and fall of the patient's hospital gown while you appear to be taking their pulse. Normal is between 12 and 20. In general, this measurement offers no relevant information for the routine examination. However, particularly in the setting of cardio-pulmonary illness, it can be a very reliable marker of disease activity.

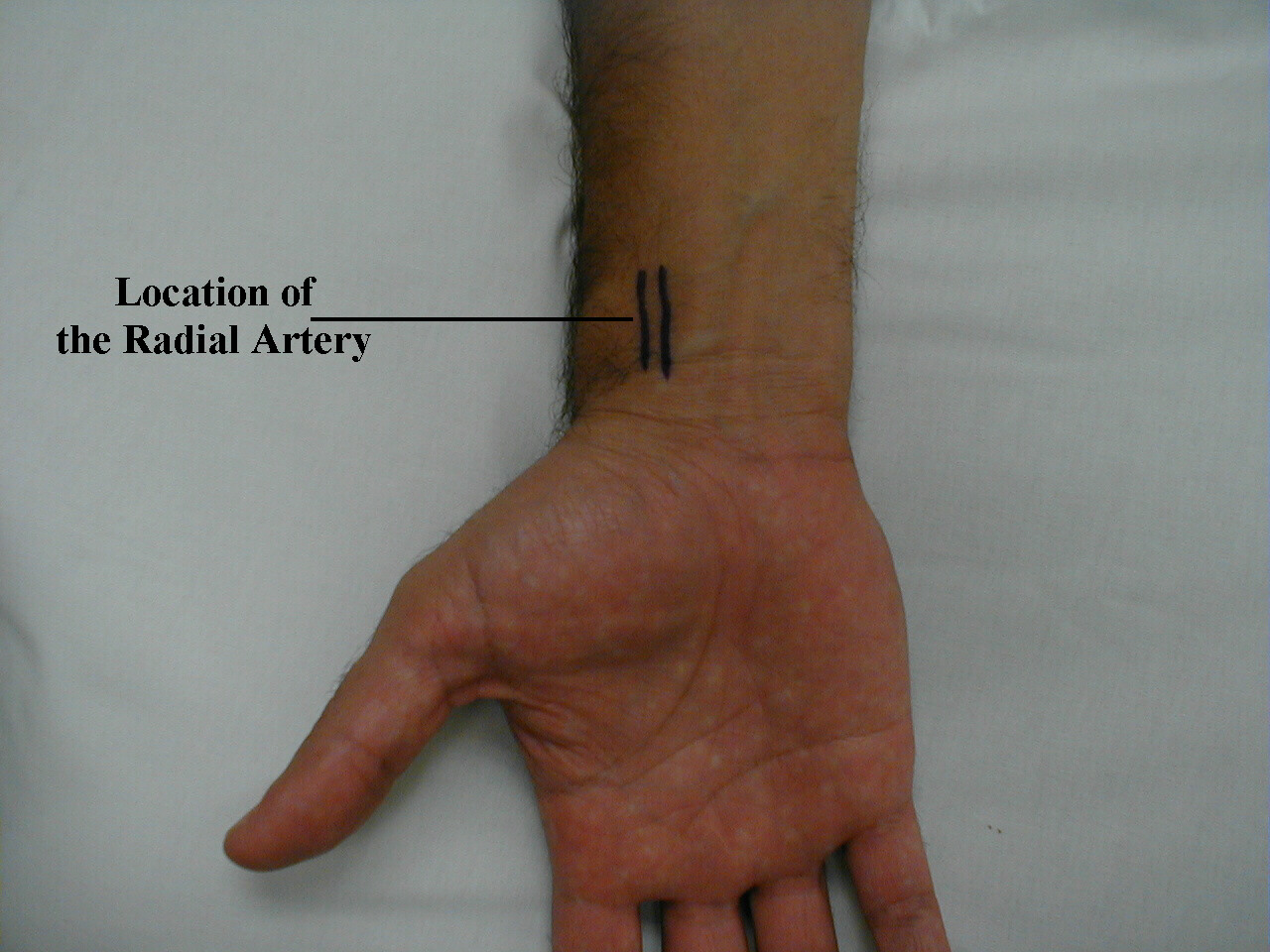

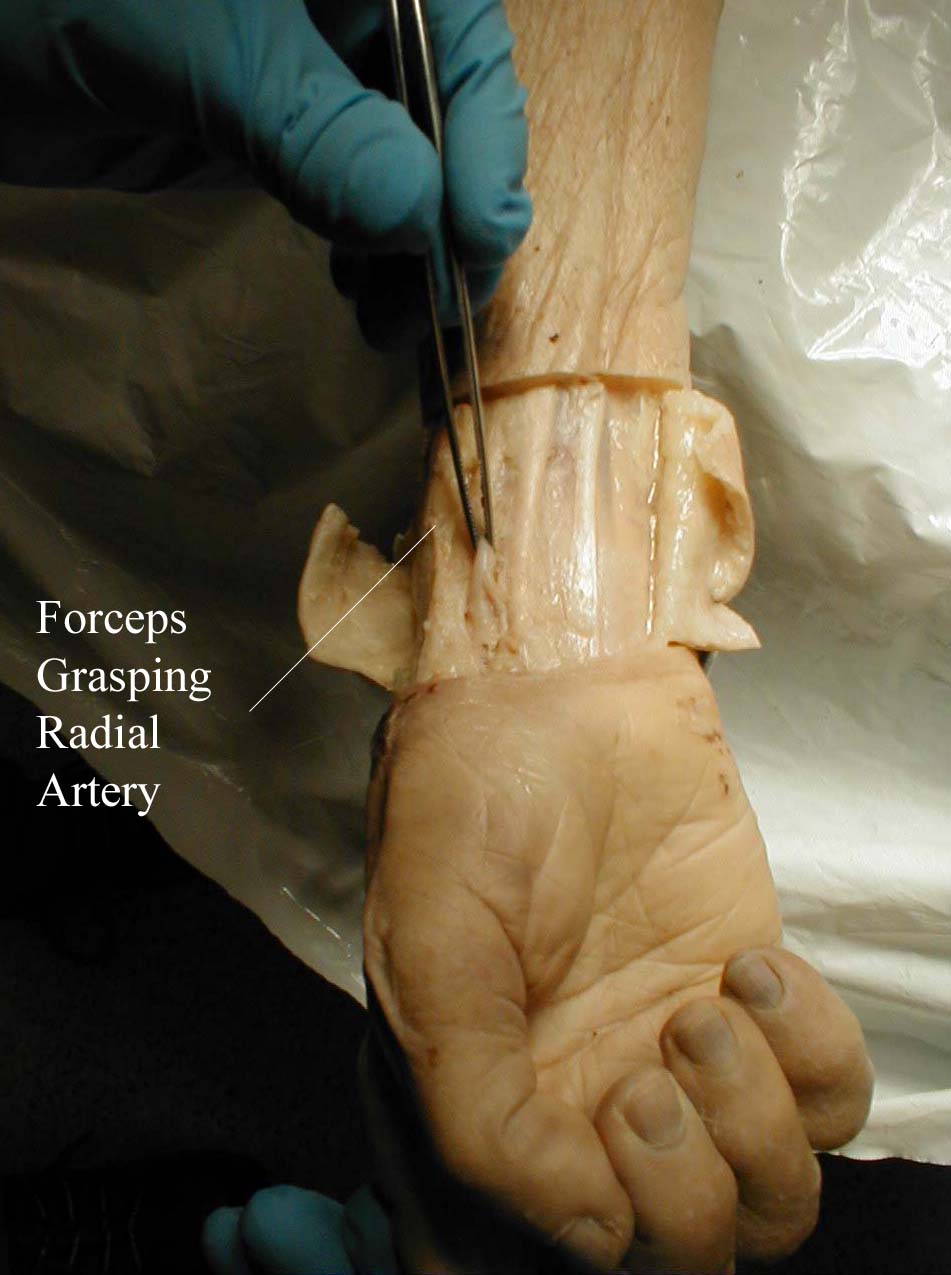

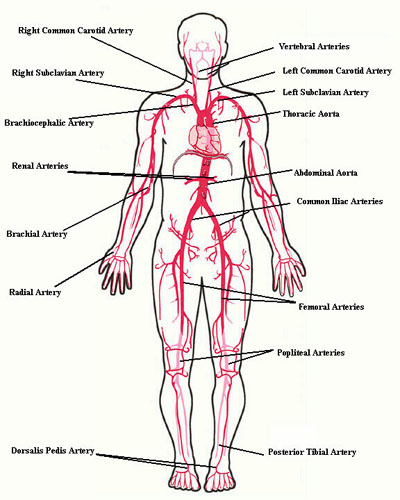

Pulse: This can be measured at any place where there is a large artery (e.g. carotid, femoral, or simply by listening over the heart), though for the sake of convenience it is generally done by palpating the radial impulse. You may find it helpful to feel both radial arteries simultaneously, doubling the sensory input and helping to insure the accuracy of your measurements. Place the tips of your index and middle fingers just proximal to the patients wrist on the thumb side, orienting them so that they are both over the length of the vessel.

Frequently, you can see transmitted pulsations on careful visual inspection of this region, which may help in locating this artery. Upper extremity peripheral vascular disease is relatively uncommon, so the radial artery should be readily palpable in most patients. Push lightly at first, adding pressure if there is a lot of subcutaneous fat or you are unable to detect a pulse. If you push too hard, you might occlude the vessel and mistake your own pulse for that of the patient. During palpation, note the following:

- Quantity: Measure the rate of the pulse (recorded in beats per minute). Count for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 (or 15 seconds x 4). If the rate is particularly slow or fast, it is probably best to measure for a full 60 seconds in order to minimize the impact of any error in recording over shorter periods of time. Normal is between 60 and 100.

- Regularity: Is the time between beats constant? In the normal setting, the heart rate should appear metronomic. Irregular rhythms, however, are quite common. If the pattern is entirely chaotic with no discernable pattern, it is referred to as irregularly irregular and likely represents atrial fibrillation. Extra beats can also be added into the normal pattern, in which case the rhythm is described as regularly irregular. This may occur, for example, when impulses originating from the ventricle are interposed at regular junctures on the normal rhythm. If the pulse is irregular, it's a good idea to verify the rate by listening over the heart (see cardiac exam section). This is because certain rhythm disturbances do not allow adequate ventricular filling with each beat. The resultant systole may generate a rather small stroke volume whose impulse is not palpable in the periphery.

- Volume: Does the pulse volume (i.e. the subjective sense of fullness) feel normal? This reflects changes in stroke volume. In the setting of hypovolemia, for example, the pulse volume is relatively low (aka weak or thready). There may even be beat to beat variation in the volume, occurring occasionally with systolic heart failure.

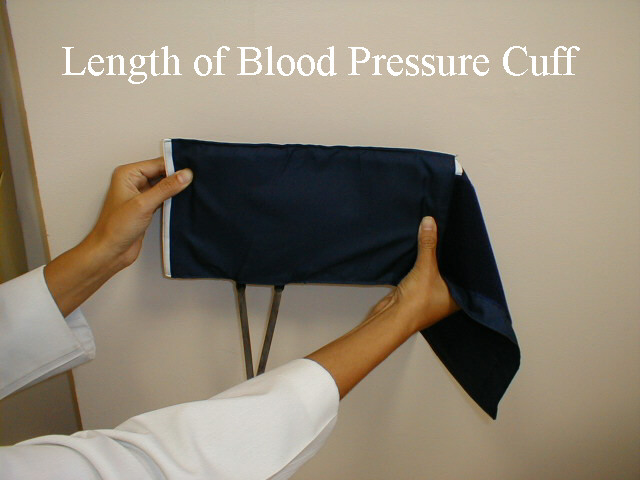

Blood Pressure: Blood pressure (BP) is typically measured using an anaeroid manometer, with readings reported in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg). While most BP readings in hospitals and clinics are initially taken with digital machines, it's still relevant to learn how to use manual cuffs, as clinicians will need to check the validity of digital readings on occasion (e.g. when BP unexpectedly high or low). The size of the BP cuff will affect the accuracy of these readings. The inflatable bladder, which can be felt through the vinyl covering of the cuff, should reach roughly 80% around the circumference of the arm while its width should cover roughly 40%. If it is too small, the readings will be artificially elevated. The opposite occurs if the cuff is too large. Clinics should have at least 2 cuff sizes available, normal and large. Try to use the one that is most appropriate, recognizing that there will rarely be a perfect fit.

Click here to access Unit one Content..

Topic 3: GENERAL EXAMINATION AND VITAL SIGNS (Cont')

Blood Pressure Cuffs

In order to measure the BP, proceed as follows:

- The patient should be seated, ideally resting for 5 minutes prior to measuring their blood pressure. Legs should be uncrossed, feet placed flat on the floor.Antecubital Fossa

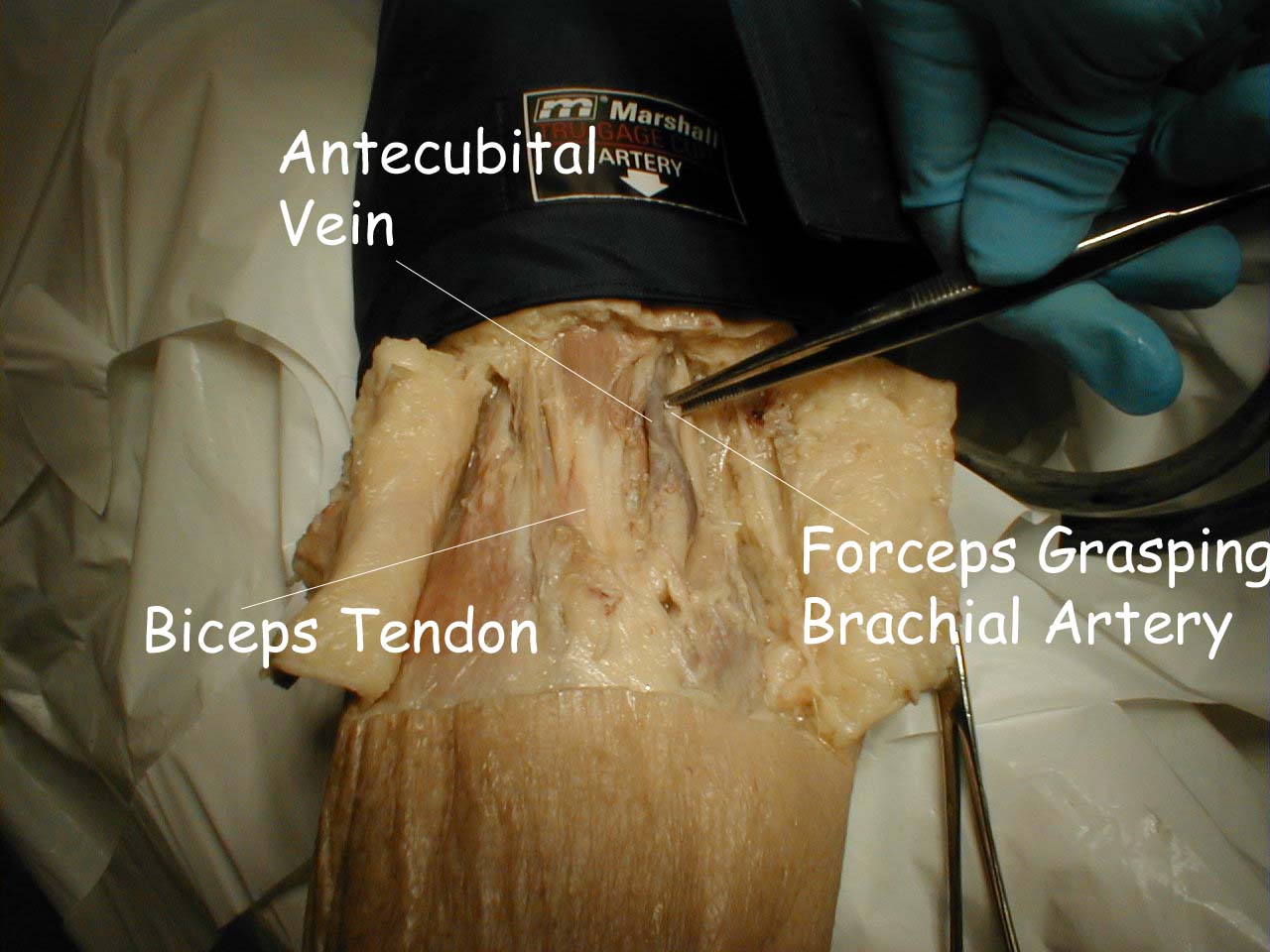

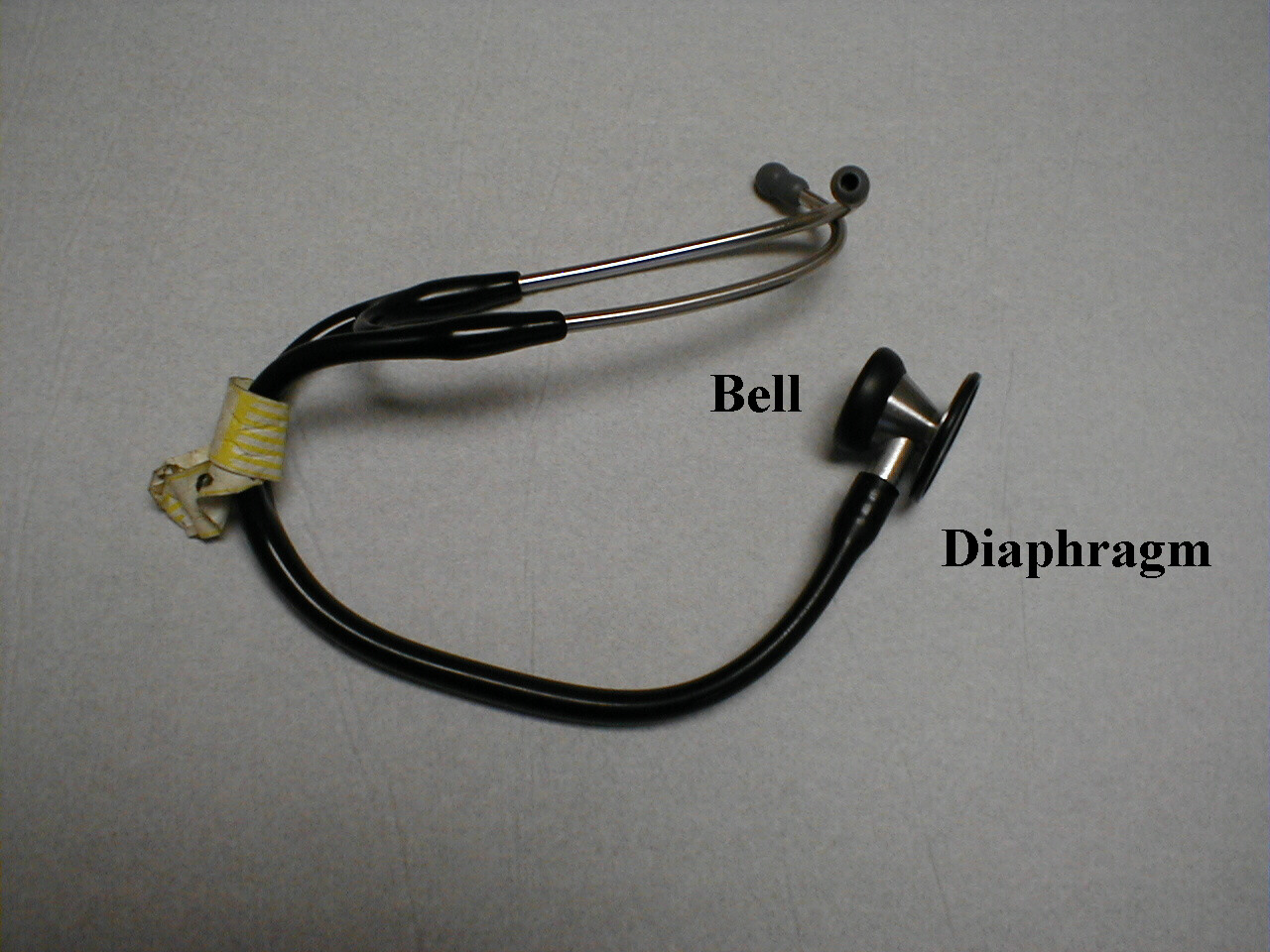

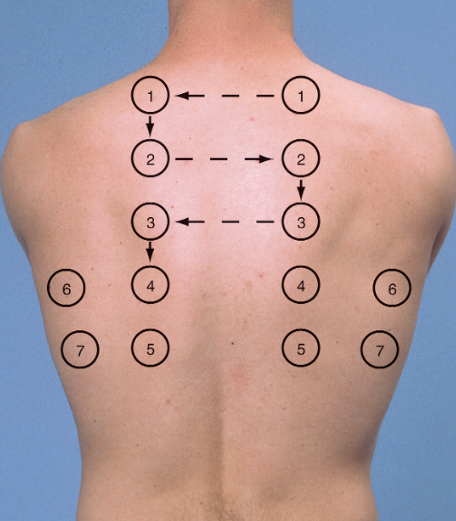

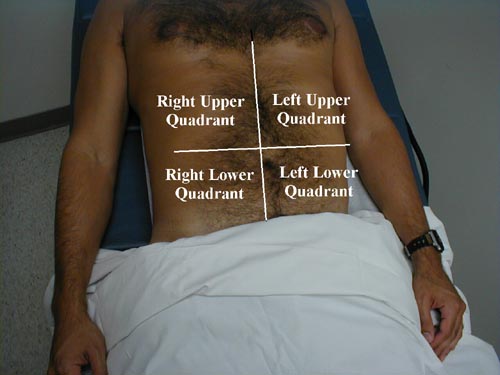

The pictures below demonstrate the antecubital fossa anatomy (surface anatomy on the left, gross anatomy on the right).

- The cuff should be placed directly on the skin (i.e. do not put it over clothes). Sliding a loose fitting t-shirt up so that the skin is exposed is fine. However, try not to roll tight fitting shirts up over the bicep. In that setting, it’s better to have the patient take their shirt off (using a gown to keep the rest of their body covered).